Chapter 3 - Basic Python syntax

Contents

Chapter 3 - Basic Python syntax#

2022 August 25

This chapter explains foundational Python syntax that you can reuse to accomplish many basic data creation, importing, and exporting tasks.

Variable assignment#

In Python, data are saved in variables. Variable names should be simple and descriptive.

The process is saving something in a variable is called variable assignment.

Assign a variable by typing its name to the left of the equals sign. Whatever is written to the right of the equals sign will be saved in the variable.

Save a single number inside of a variable named with a single letter. You could read the below lines as “x is defined as one”, “two is assigned to y”, or most simply put, “z is three”:

# define one variable

x = 1

# assign multiple variables in a single code cell

x = 1

y = 2

z = 3

Use print() to show it on the screen#

print(x)

1

# "call" the variables directly!

x

1

y

2

print(x / y * z)

1.5

x / y * z

1.5

Functions, arguments, and methods#

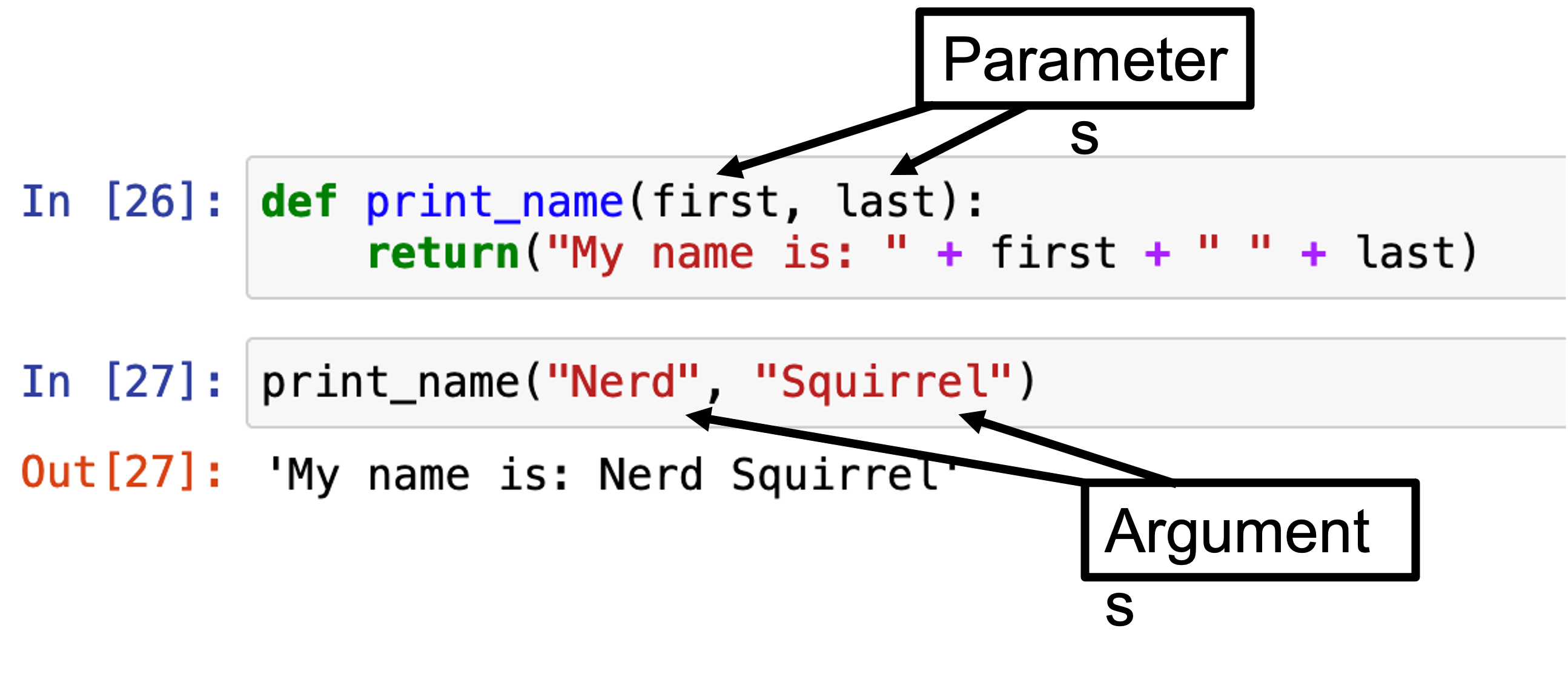

Functions, arguments, and methods form the core user framework for Python programming.

Functions: Perform self-contained actions on a thing.

Argument(s): The “things” (text, values, expressions, datasets, etc.)

Note “parameters” are the variables as notated during function definition. Arguments are the values we pass into these placeholders while calling the function.

# Example custom function

def print_name(first, last):

return("My name is: " + first + " " + last)

print_name("Nerd", "Squirrel")

'My name is: Nerd Squirrel'

Methods: Type-specific functions (i.e., can only use a specific type of data and not other types). Use “dot” notation to utilize methods on a variable or other object.

For example, you will type

gap = pd.read_csv('data/gapminder-FiveYearData.csv')to use theread_csv()method from the pandas library (imported as the aliaspd) to load the Gapminder data.

Data types#

Everything in Python has a type which determines how we can use and manipulate it. Data are no exception! Be careful, it is easy to get confused when trying to complete multiple tasks that use lots of different variables!

Use the type function to get the type of any variable if you’re unsure. Below are four core data types:

str: Character string; text. Always wrapped in quotations (single or double are fine)bool: BooleanTrue/False.Trueis stored under the hood as 1,Falseis stored as 0float: Decimals (floating-point)int: Whole numbers (positive and negative, including zero)

# 1. String data

x1 = "This is string data"

print(x1)

print(type(x1))

This is string data

<class 'str'>

# 2. Boolean data

x2 = True

print(x2)

print(type(x2))

True

<class 'bool'>

# 3. float (decimals)

# use a decimal to create floats

pi = 3.14

print(pi)

print(type(pi))

3.14

<class 'float'>

# 4. integer (whole numbers)

# do not use a decimal for integers

amount = 4

print(amount)

print(type(amount))

4

<class 'int'>

String addition versus integer addition#

# character strings

'1' + '1'

'11'

# integers

1 + 1

2

Data structures#

Data can be stored in a variety of ways. Regardless, we can index (positionally reference) a portion of a larger data structure or collection.

Python is zero-indexed!#

Python is a zero-indexed programming language and means that you start counting from zero. Thus, the first element in a collection is referenced by 0 instead of 1.

Four structures are discussed below:

Lists are ordered groups of data that are both created and indexed with square brackets

[]Dictionaries are unordered groups of “key:value” pairs. Use the key to access the value. Curly braces

{}are used to create and index dictionariesCharacter strings can contain text of virtually any length

Data Frames are tabular data organized into rows and columns. Think of an MS Excel spreadsheet!

1. List#

# Define a list with with square brackets. This list contains two character strings 'shark' and 'dolphin'

animals = ['shark', 'dolphin']

animals[0]

'shark'

# Call the second thing (remember Python is zero-indexed)

animals[1]

'dolphin'

Lists can contain elements of almost any data type, including other lists!

When this is the case, we can use multi-indices to extract just the piece of data we want. For example, to return only the element “tree”:

# Lists can contain other structures, such as other lists

# To get an element from a list within a list, double-index the original list!

animals = ['shark', 'dolphin', ['dog', 'cat'], ['tree', 'cactus']]

print(animals[3][0])

tree

Or, to just return the element “cat”:

# print this 'animals' list

print(animals)

['shark', 'dolphin', ['dog', 'cat'], ['tree', 'cactus']]

# print just the 3rd thing - the sublist containing 'dog' and 'cat'

print(animals[2])

['dog', 'cat']

# print only 'cat'

print(animals[2][1])

cat

Lists can also contain elements of different types:

# Define a heterogeneous list

chimera = ['lion', 0.5, 'griffin', 0.5]

print(type(chimera[0]))

print(type(chimera[1]))

<class 'str'>

<class 'float'>

2. Dictionary#

# Define two dictionaries - apple and orange

apple = {'name': 'apple', 'color': ['red', 'green'], 'recipes': ['pie', 'salad', 'sauce']}

orange = {'name': 'orange', 'color': 'orange', 'recipes': ['juice', 'marmalade', 'gratin']}

apple

{'name': 'apple',

'color': ['red', 'green'],

'recipes': ['pie', 'salad', 'sauce']}

orange

{'name': 'orange',

'color': 'orange',

'recipes': ['juice', 'marmalade', 'gratin']}

Combine two dictionaries into one by placing them in a list value [apple, orange], with a key named fruits. Call the key to see the value(s)!

fruits = {'fruits': [apple, orange]}

fruits

{'fruits': [{'name': 'apple',

'color': ['red', 'green'],

'recipes': ['pie', 'salad', 'sauce']},

{'name': 'orange',

'color': 'orange',

'recipes': ['juice', 'marmalade', 'gratin']}]}

To index just “juice” - under the ‘recipes’ key for the orange dictionary, combine dictionary key and list techniques to tunnel into the hierarchical structure of the dictionary and extract just what you want:

# Call the newly combined dictionary

fruits

{'fruits': [{'name': 'apple',

'color': ['red', 'green'],

'recipes': ['pie', 'salad', 'sauce']},

{'name': 'orange',

'color': 'orange',

'recipes': ['juice', 'marmalade', 'gratin']}]}

# Reference the 'fruits' key

fruits['fruits']

[{'name': 'apple',

'color': ['red', 'green'],

'recipes': ['pie', 'salad', 'sauce']},

{'name': 'orange',

'color': 'orange',

'recipes': ['juice', 'marmalade', 'gratin']}]

# Index the second thing (orange)

fruits['fruits'][1]

{'name': 'orange',

'color': 'orange',

'recipes': ['juice', 'marmalade', 'gratin']}

# Call the 'recipes' key from 'orange' to see the items list

fruits['fruits'][1]['recipes']

['juice', 'marmalade', 'gratin']

# Return the first thing from the 'recipes' key of the 'orange' dictionary inside of 'fruits'!

fruits['fruits'][1]['recipes'][0]

'juice'

Data import#

Python offers a variety of methods for importing data. Thankfully, it is quite straightforward to import data from .csv and .txt files. Other formats, such as .xml and .json, are also supported.

Below, let’s import:

Text from a .txt file

A dataframe from a .csv file

Import text data as a character string#

Import text as a single string using the open().read() Python convention.

Review your basic building blocks from above:

frankis the name of the variable we will save the text inside ofopenis the function we will use to open the text file'data/frankenstein.txt'is the argument that we provide to theopenfunction. This matches thefilepath argument and needs to contain the location for the Frankenstein book..read()reads the file as text.

A note about importing data into Google Colab#

Navigating Google Colab’s file system can be challenging since it is slightly different from working on your local machine.

Run the code below to import the dataset into a temporary subfolder named “data” inside of the main Colab “/content” directory.

Run Steps 1-3 below to save a data file in your Google Drive, which can then be importend to your Colab environment

NOTE: Colab is a temporary environment with an idle timeout of 90 minutes and an absolute timeout of 12 hours.

There are other ways to use Colab’s file system, such as mounting your Google Drive, but if you are having trouble in Colab refer back to these steps to import data used in this bootcamp. Contact SSDS if you want to learn more.

# Step 1. Create the directory

!mkdir data

# Step 2. “List” the contents of the current working directory

!ls

# Step 3. Use wget to download the data file

# learn more about wget: https://www.gnu.org/software/wget/?

# !wget -P data/ https://raw.githubusercontent.com/EastBayEv/SSDS-TAML/main/fall2022/data/frankenstein.txt

mkdir: data: File exists

1_How_to_use_this_book.ipynb

2_Python_environments.ipynb

3_Basic_Python_syntax.ipynb

4_Numeric_data_wrangling.ipynb

5_Data_visualization_essentials.ipynb

6_Core_concepts_vocabularies.ipynb

7_English_text_preprocessing_basics_applications.ipynb

8_spaCy_textaCy.ipynb

9_BERTopic.ipynb

Appendix.ipynb

Solutions.ipynb

data

img

frank = open('data/frankenstein.txt').read()

# print(frank)

# print only the first 1000 characters

print(frank[:1000])

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Frankenstein, by Mary Wollstonecraft (Godwin) Shelley

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you

will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before

using this eBook.

Title: Frankenstein

or, The Modern Prometheus

Author: Mary Wollstonecraft (Godwin) Shelley

Release Date: 31, 1993 [eBook #84]

[Most recently updated: November 13, 2020]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

Produced by: Judith Boss, Christy Phillips, Lynn Hanninen, and David Meltzer. HTML version by Al Haines.

Further corrections by Menno de Leeuw.

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FRANKENSTEIN ***

Frankenstein;

or, the Modern Prom

Import data frames with the pandas library#

Data frames are programming speak for tabular spreadsheets organized into rows and columns and often stored in useful formats such as .csv (i.e., a spreadsheet)

.csv stands for “comma-separated values” and means that these data are stored as text files with a comma used to delineate column breaks.

For this part, we will use the pandas Python library. Remember how to install user-defined libraries from Chapter 2? This is a two step process.

# Step 1. Physically download and install the library's files (unhashtab the line below to run)

# !pip install pandas

# Step 2. link the pandas library to our current notebook

# pd is the alias, or shorthand, way to reference the pandas library

import pandas as pd

Now, you can use dot notation (type pd.)to access the functions within the pandas library.

We want the read.csv method. Like the .txt file import above, we must provide the file path of the location of the .csv file we want to import.

Save it in the variable named gap

What is Gross Domestic Product? (GDP)#

GDP is a general estimate of global societal well-being. Learn more about GDP here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gross_domestic_product.

Learn more about GDP “per capita” (per person): https://databank.worldbank.org/metadataglossary/statistical-capacity-indicators/series/5.51.01.10.gdp

# Colab users: grab the data! Unhashtag the line below

# !wget -P data/ https://raw.githubusercontent.com/EastBayEv/SSDS-TAML/main/fall2022/data/gapminder-FiveYearData.csv

gap = pd.read_csv("data/gapminder-FiveYearData.csv")

# View the data

print(gap)

country year pop continent lifeExp gdpPercap

0 Afghanistan 1952 8425333.0 Asia 28.801 779.445314

1 Afghanistan 1957 9240934.0 Asia 30.332 820.853030

2 Afghanistan 1962 10267083.0 Asia 31.997 853.100710

3 Afghanistan 1967 11537966.0 Asia 34.020 836.197138

4 Afghanistan 1972 13079460.0 Asia 36.088 739.981106

... ... ... ... ... ... ...

1699 Zimbabwe 1987 9216418.0 Africa 62.351 706.157306

1700 Zimbabwe 1992 10704340.0 Africa 60.377 693.420786

1701 Zimbabwe 1997 11404948.0 Africa 46.809 792.449960

1702 Zimbabwe 2002 11926563.0 Africa 39.989 672.038623

1703 Zimbabwe 2007 12311143.0 Africa 43.487 469.709298

[1704 rows x 6 columns]

gap

| country | year | pop | continent | lifeExp | gdpPercap | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Afghanistan | 1952 | 8425333.0 | Asia | 28.801 | 779.445314 |

| 1 | Afghanistan | 1957 | 9240934.0 | Asia | 30.332 | 820.853030 |

| 2 | Afghanistan | 1962 | 10267083.0 | Asia | 31.997 | 853.100710 |

| 3 | Afghanistan | 1967 | 11537966.0 | Asia | 34.020 | 836.197138 |

| 4 | Afghanistan | 1972 | 13079460.0 | Asia | 36.088 | 739.981106 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 1699 | Zimbabwe | 1987 | 9216418.0 | Africa | 62.351 | 706.157306 |

| 1700 | Zimbabwe | 1992 | 10704340.0 | Africa | 60.377 | 693.420786 |

| 1701 | Zimbabwe | 1997 | 11404948.0 | Africa | 46.809 | 792.449960 |

| 1702 | Zimbabwe | 2002 | 11926563.0 | Africa | 39.989 | 672.038623 |

| 1703 | Zimbabwe | 2007 | 12311143.0 | Africa | 43.487 | 469.709298 |

1704 rows × 6 columns

Getting help#

The help pages in Python are generally quite useful and tell you everything you need to know - you just don’t know it yet! Type a question mark ? before a funciton to view its help pages.

# ?pd.read_csv

Error messages#

Python’s learning curve can feel creative and beyond frustrating at the same time. Just remember that everyone encounters errors - lots of them. When you do, start debugging by investigating the type of error message you receive.

Scroll to the end of the error message and read the last line to find the type of error.

Helpful debugging tools/strategies:

Googling the error text, and referring to a forum like StackOverflow

(IDE-dependent) Placing breakpoints in your program and using the debugger tool to step through the program

Strategically place print() statements to know where your program is reaching/failing to reach

Ask a friend! A fresh set of eyes goes a long way when you’re working on code.

Restart your IDE and/or your machine.

Exercises#

Unhashtag the line of code for each error message below

Run each cell

Inspect the error messages. Are they helpful?

Syntax errors#

Invalid syntax error

You have entered invalid syntax, or something python does not understand.

# x 89 5

Indentation error

Your indentation does not conform to the rules.

Highlight the code in the cell below and press command and / (Mac) or Ctrl and / on Windows to block comment/uncomment multiple lines of code:

# def example():

# test = "this is an example function"

# print(test)

# return example

Runtime errors#

Name error

You try to call a variable you have not yet assigned

# p

Or, you try to call a function from a library that you have not yet imported

# example()

Type error

You write code with incompatible types

# "5" + 5

Index error

You try to reference something that is out of range

my_list = ['green', True, 0.5, 4, ['cat', 'dog', 'pig']]

# my_list[5]

File errors#

File not found

You try to import something that does not exist

# document = open('fakedtextfile.txt').read()

Exercises#

Define one variablez for each of the four data types introduced above: 1) string, 2) boolean, 3) float, and 4) integer.

Define two lists that contain four elements each.

Define a dictionary that containts the two lists from #2 above.

Import the file “dracula.txt”. Save it in a variable named

dracImport the file “penguins.csv”. Save it in a variable named

penFigure out how to find help to export just the first 1000 characters of

dracas a .txt file named “dracula_short.txt”Figure out how to export the

pendataframe as a file named “penguins_saved.csv”

If you encounter error messages, which ones?

Pro tip: See the Solutions chapter for code to copy files from your Colab environment to your Google Drive!

Numeric data wrangling#

Importing numeric data from a .csv file is one thing, but wrangling it into a format that suits your needs is another. Read Chapter 4 “Numeric data wrangling” to learn how to use the pandas library to subset numeric data!

Chapter 7 contains information about preprocessing text data.